Satiety Response to High-Palatable Foods

Physiological mechanisms and appetite regulation in response to discretionary foods

Satiety Mechanisms: Basic Physiology

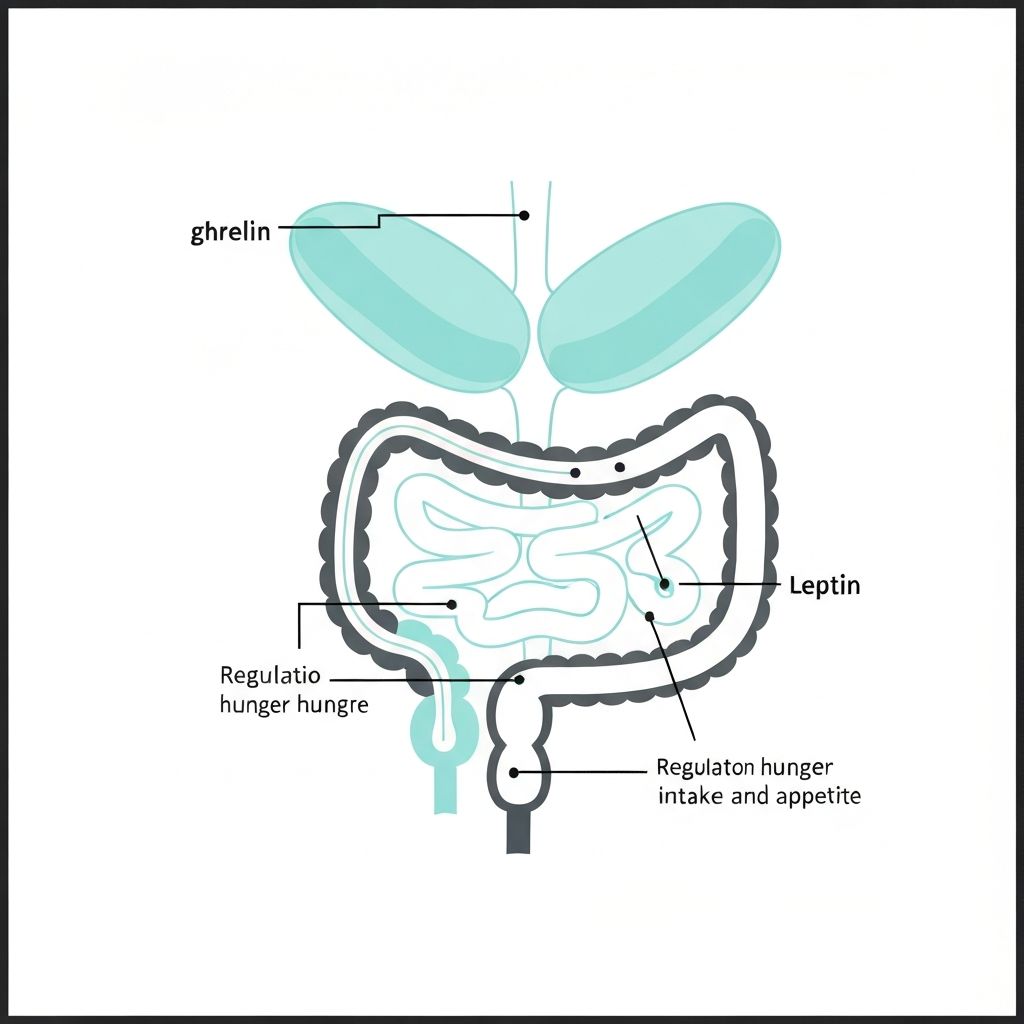

Satiety—the sensation of fullness and satisfaction following food consumption—is regulated by multiple physiological signals. The body uses both mechanical feedback (stomach distension) and chemical signals (hormones and neurological pathways) to communicate satiation.

Key hormonal regulators include ghrelin (often described as the "hunger hormone," which increases appetite) and leptin and peptide YY (which promote satiety). Additionally, cholecystokinin (CCK) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) signal fullness in response to nutrient consumption.

These regulatory systems evolved to maintain energy balance across variable food availability. However, the modern food environment—characterised by high-energy-density, highly palatable foods—presents conditions quite different from those under which these regulatory systems evolved.

High Palatability and Reward Pathways

Foods engineered for high palatability—combinations of sugar, fat, and salt—activate reward centres in the brain beyond the normal satiety response. These foods stimulate the dopaminergic reward system, creating separate motivation for consumption independent of energy needs.

The palatability-driven desire to consume can override or supersede physiological satiety signals. A person may feel physically full yet continue eating a highly palatable food because the reward signal is stronger than the satiation signal. This dissociation between physical fullness and psychological desire to eat is well-documented in research on eating behaviour.

This distinction between energy density and satiety per calorie helps explain why discrete "treats" present a specific intake challenge. The energy consumed may be substantial, yet the satiety signal generated may be insufficient to prevent further consumption or to reduce intake at subsequent eating occasions.

Satiety Response and Macronutrient Composition

Different macronutrients trigger different satiety responses. Protein generally produces the strongest satiety signal per calorie consumed, followed by carbohydrates, with fat producing the weakest satiety response relative to energy content.

Discretionary foods typically contain combinations of sugar (carbohydrate) and fat, often with relatively little protein. This macronutrient profile generates weaker satiety signals per calorie than would a comparable energy amount from protein-rich or high-fibre foods. Thus, a 250-calorie chocolate bar may produce considerably less satiation than 250 calories from chicken and vegetables.

Additionally, fibre—present in higher quantities in nutrient-dense foods but largely absent in discretionary foods—contributes significantly to satiety through multiple mechanisms including gastric distension and visceral signalling. The lack of fibre in treats further reduces their satiety potential per calorie.

Taste, Habituation, and Reward Adaptation

The hedonic (pleasure-based) response to foods is not static. Repeated exposure to a particular taste or food results in habituation—a gradual reduction in the pleasure response. Initially, a treat may produce strong hedonic reward; with repeated consumption, the same food generates progressively weaker pleasure.

However, research documents that exposure to variety in highly palatable foods can prevent habituation. The sensory-specific satiety mechanism—whereby satiation is greater for recently consumed foods and less for novel foods—means that changing the specific treat consumed (chocolate bar today, crisps tomorrow) may circumvent this habituation effect.

This dietary variety effect may contribute to overconsumption patterns in modern food environments where discretionary foods come in numerous flavours and varieties. The body's satiety mechanisms, which may previously have worked through habituation to a limited set of foods, face challenges in environments with unlimited variety.

Liquid Calories and Satiety

Beverages high in sugar and energy present a particular satiety challenge. Liquid calories—from soft drinks, sweetened coffee beverages, and fruit juices—contribute substantially to daily energy intake yet produce minimal satiety signals. Research consistently shows that people do not reduce intake of solid foods when consuming liquid calories; instead, these calories are often consumed in addition to regular intake.

This represents a situation where energy intake from discretionary sources (sugary drinks) does not trigger corresponding reduction in other eating, leading to net positive energy balance change. The sensory characteristics of liquids—lack of resistance to chewing, rapid transit through the GI tract, absence of mechanical distension signals—make them particularly problematic for satiety regulation.

Individual Variation in Satiety Response

While these physiological mechanisms are generally conserved across humans, individual variation in satiety responsiveness is substantial. Some people report strong satiety responses to foods; others report relatively weak satiation. This variation has genetic, experiential, and contextual components.

Research documents that individuals with weaker satiety responses to energy-dense, palatable foods face greater challenges in regulating intake of these items. Conversely, individuals with strong satiety responses may find that modest portions of treats naturally produce adequate fullness signals.

This individual variation underscores why population-level observations and averages may not predict individual experience. What represents a "moderate" amount of a treat for one person may feel insufficient or excessive for another, based partly on differences in satiety physiology.